DX listening has been around as long as radio itself. The origin of the term “DX” is the subject of some debate, but it is generally accepted that DX either represented “distant exchange” in old telephone parlance; or simply an abbreviated term for “distance.”

One of the earliest distant radio signal transmissions occurred in 1906, when Canadian Reginald Fessenden broadcast his famous Christmas Eve radio program from Brant Rock near Boston with reports of reception from ships in the Caribbean.

DXing developed as amateur radio operators and engineers worked to assess both the distance capabilities and quality of radio transmissions. The commercial opportunities associated with strong, powerful, long haul broadcasts were enormous.

Pioneers like Fessenden, David Sarnoff and Harold Beverage and others worked to make radio broadcasting into the creative cultural and information industry it is today. In a 1968 interview Beverage, inventor of the famous wave antenna (for receiving) that bears his name, described his early DX experimentation in radio:

“I swiped a piece of galena (crystal) from the high-school laboratory. About 1909 I was picking up signals from ships. Ships going to and from Europe would pass by my island, not too far out, so I was interested in copying these ship stations… let’s say I just got interested in wireless. Back on the farm I thought it a lot more fun to be messing around with wireless than it would be pitching hay.”1

Later, in April of 1912, Beverage would snag the ultimate DX listening catch: the Titanic’s calls for help. David Sarnoff was also on duty as the designated shore operator that night, and thus those two greats from the founding days of radio had their paths cross for the first of many times.

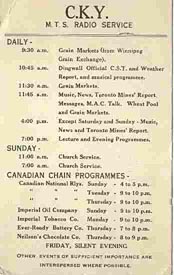

Commercial broadcasting began in earnest in the 1920s. Even in those seminal days of radio with rudimentary equipment, AM broadcast signals traveled a surprising distance. By the middle of that decade powerful, clear channel, stations occupied several spots on the North American dial. Stations in the central part of the continent could be heard on both coasts on a good night.

Local newspapers in all cities listed the frequencies and schedules of far-flung stations. The Lowell, Massachusetts Courier Citizen, for instance, even listed the nighttime schedule of CNRC in Calgary, over 2000 miles distant – along with the broadcast times of other stations in cities like New York, Chicago and St. Louis.2

A casual listener sought out those stations for their programming content. But the true DXer listened specifically because those stations were far away. Like fishing – where some people fish for food and others fish simply for the sport of it – DXers were always after the thrill of the “catch.” The more difficult a station was to hear, the more valuable it was to a DXer.

It was during these founding years that “professional” DXers commenced the study of radio wave propagation in earnest. By 1924 and 1925 British scientist Edward Appleton began to use instruments to explore the upper atmosphere and its relationship to radio waves.

A solar eclipse in 1927 gave Appleton conclusive proof that the Sun played a role in radio wave propagation. By the mid-1940s Appleton and others had discovered the relationship between radio waves and sunspot activity. This critical discovery earned Appleton the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1947.

As scientists were learning about the physics of radio wave propagation, broadcast DXers were becoming more and more expert in distant reception of stations in their specialty radio band.

When hearing the strongest station on each frequency became less of a challenge, DXers worked at hearing the weaker stations in the background. They developed strategies, circuits and antennas that allowed them to go beyond the easiest and most powerful stations to hear the really rare and exotic DX.

One technique was to spend Sunday nights or, more correctly, Monday mornings at the radio dials. It was during these times that the powerful continental radio stations often shut down their transmitters for maintenance. These “silent periods” afforded DXers opportunities to hear, interference free, what was usually masked by the powerful signals from those broadcasting giants.

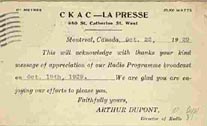

While DXers were proud of their accomplishments, Broadcasters too prided themselves in their ability to send their signals to far-flung listeners. The broadcasters and the DX listeners enjoyed a symbiotic relationship, as they communicated and cooperated with one another.

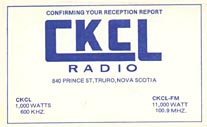

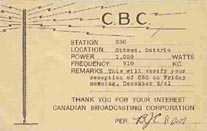

Amateur radio operators call confirmation of a radio contact a QSL. DX listeners adopted this term also, and radio stations regularly received reception reports from DXers, accompanied by requests for stations to verify the report by replying with QSL postcards.

Starting in 1924, the EKKO Company of Chicago fueled a short-lived collectors’ craze in radio verification stamps. These “EKKO stamps” were provided to radio stations, and listeners could purchase an album from EKKO in which to mount the stamps. Radio stations would send listeners a card with the stamp as proof of reception.

The collecting of stamps waned in the 1930s, but the quest for QSL cards continued, becoming a significant complement to the DXing hobby. Soon, DXers from all parts of the world began to congregate themselves into clubs and associations, to share their radio loggings, report QSLs received, discuss receiver construction ideas and antenna projects.

As the medium of radio broadcasting took off in the 1920s, so did developments in equipment. Canadian Edward Rogers Sr. introduced the first AC powered radio in the world at the CNE in Toronto in 1925. The “Rogers Batteryless” radio allowed ordinary people to simply plug in their sets to house current and instantly become part of the phenomenon. Until then radios around the world had been powered by big auto batteries.

Manufacturers like Rogers, Crosley, Canadian General Electric and others put their receivers into production, and DXers were able to compile still higher totals of stations heard and confirmed. Following World War II a glut of military surplus radios hit the used market, and DXers improved their listening ability still further with the addition of cheap but highly effective receivers.

Probably the most revered receiver from the 1950s and 60s was, and still is, the Collins-designed R390A/URR. Made by several manufacturers under contract to the U.S. military, this radio was once considered “Top Secret” because of its exceptional performance.

Many serious broadcast DXers managed to get their hands on the famed R390, and the receiver is revered by many as superior to the solid-state radios produced today. Hundreds of them have been restored and maintained, and occupy prominent places in the homes of DXers all over the world.

As technology continued to evolve in the 1950s, many broadcasters began to populate the FM band. Not widely known for traveling long distances, VHF FM signals can indeed, when the conditions are just right, travel hundreds and even thousands of miles. TV signals share these characteristics, and where there are DX signals, there are DXers!

A milestone was celebrated in the FM DX community in June of 2003, as reception was finally confirmed, for the first time ever, of North American FM stations in Europe. DXers in the United Kingdom heard CKLE in New Brunswick, and CBTB, CBTR and VOCM in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Trans-Atlantic reception of Canadian AM stations was quite commonplace. For instance 50,000 watt CFNB in Fredericton was a regular in Scandiavia during the right time of year. But FM reception across the pond was a different story.

The 2003 Trans-Atlantic catch was an event for which FM DXers had been waiting for a long time, and one which is not likely to be repeated soon, as the atmospheric and ionospheric conditions required for this type of long distance FM reception are very rare.

After more than 50 years of DXing the FM band and almost 100 years of DXing on AM, hobbyists continue to push the limits of the ionosphere and themselves. With the plethora of urban electrical noise from computers and other devices, DXers have taken to traveling to prime listening locations to pursue their hobby in an environment free from man-made interference.

These trips have come to be called DX-peditions, and feature teams of highly-skilled radio listeners and advanced antenna systems. Locales on both of Canada’s coasts have become prime locations for DX-peditions, and even in the center of the country DXers have found prime radio real estate on which to pursue their hobby.

Interestingly, one of the most favoured antennas in use on AM band DX-peditions to this day is none other than the Beverage. Almost a century old, the Beverage antenna’s outstanding performance makes it a mainstay of any serious DXer’s antenna farm. Harold Beverage’s legacy survives and, coupled with advanced radio equipment, is able to deliver signals from half way around the world.

The broadcasting and engineering communities owe a debt of gratitude to DXers everywhere. Toronto’s CHWO (AM 740) is an example of a station that appreciates and cooperates closely with the DX community, airing test broadcasts and working with the Ontario DX Association to process reception reports and issue verifications. The ODXA also works closely with CFRB/CFRX, Toronto.

The keenest listeners of all, DXers love for radio and the radio business has, by serendipity, created a wealth of knowledge on radio propagation, and an archive of radio and TV memorabilia that resides in homes throughout the world. QSL cards, station letterhead, tape recordings of long gone announcers and their programs – all survive to this day because of the care and skill of DXers.

- Harold H. Beverage, Electrical Engineer, an oral history conducted in 1968 and 1973 by Norval Dwyer, IEEE History Center, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA.

- John D. Bowker, DX Audio Service, Lima, OH, USA, National Radio Club web site http://www.nrcdxas.org/articles/hmr0297.txt

Brent Taylor – 2003